Blackchin guitarfish use their tails to swim and advance like sharks, while other rays use their pectoral fins and 'glide' through the water.

They feed on fish and benthic invertebrates.

Rays

Identity card

Appendix II

East Atlantic, from Portugal to Angola and on to the Mediterranean Sea.

At a depth of between 9 and 100 metres.

On average 1.50 m, but can reach 2 m.

Fish and benthic invertebrates.

Nausicaa coordinates the European conservation programme for the blackchin guitarfish.

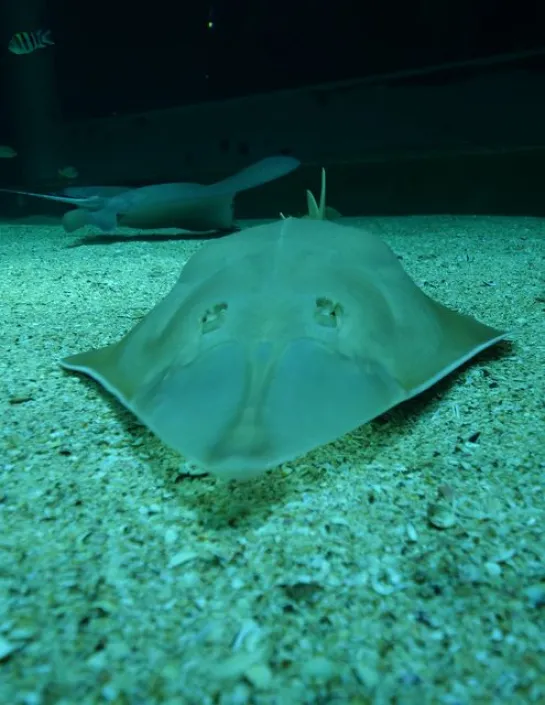

The Blackchin guitarfish burrow into the sea floor with great ease and can embed themselves.

Blackchin guitarfish use their tails to swim and advance like sharks, while other rays use their pectoral fins and 'glide' through the water.

They feed on fish and benthic invertebrates.

It is found on sandy or muddy seabeds, at depths ranging from 9 to 100 metres. It burrows into the seabed with great ease. Its beige, grainy skin makes it easy to blend in with the sand.

The blackchin guitarfish is ovoviviparous. It has one to two litters per year, each comprising 4 to 6 embryos.

Other rays that can be discovered in the High Seas tank are the oceanic manta ray, Atlantic pygmy devil rays and spotted eagle rays.

Journey on the high seas

The Ocean Mag

In the spotlight

Poissons, crevettes, requins, les animaux qui se reproduisent ou sont élevés à Nausicaá rejoignent les espaces d'exposition.

Article

Which came first, the egg or the fish? A brief overview of eggs and reproductive strategies in marine animals.

Article

Coral, the planet's largest builder, is a fragile and threatened animal.